Justin Fashanu: Football’s gay trailblazer and his last hurrah in New Zealand

The striker, who became the first openly gay professional men's footballer in 1990, finished his career with Miramar Rangers in Wellington in 1997.

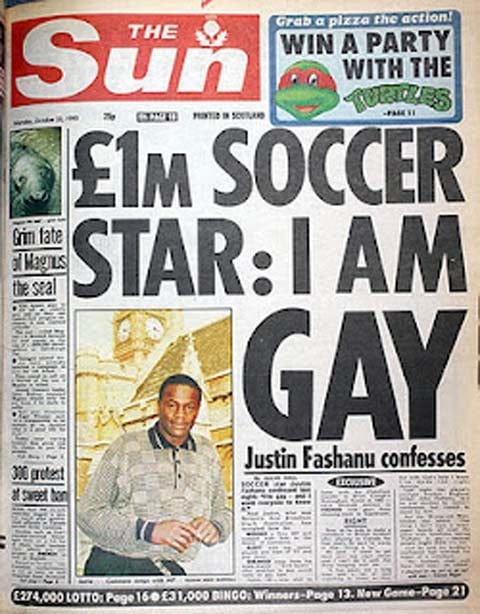

Justin Fashanu’s life was extraordinary, tumultuous and, ultimately short. Raised in foster care, his football career combusted into life at Norwich City with a stunning goal of the season against Liverpool in 1980. He went on to become Britain’s first £1 million black footballer but remains best known to this day as the first openly gay men’s professional footballer.

This week marks 25 years since Fashanu’s death. Of all the stories that could be told of his remarkable and controversial 37 years of life one that is often forgotten is that of his last season as a player, played, of all places, here in New Zealand, with Wellington-based Miramar Rangers.

This is the story of Fashanu’s Kiwi swan song.

*This story deals with the issue of suicide. Reader discretion is advised.*

Ahead of another summer of football Miramar Rangers were struggling to find a striker to spearhead their attack. An attempt to lure Mount Maunganui goal-machine Alan Lamb had failed and head coach John Cameron was struggling for options.

However, he was in luck. Out of the blue came a call from New Zealand Football development officer Glenn Turner with a too-good-to-be-true proposition.

Prior to his role at NZF, Glenn, who passed away last year, worked as a physical educator in Fashanu’s home county of Norfolk and the two were close. Turner was aware of Miramar’s striker shortage and felt Justin might be the solution. After all, he would not even be the first Fashanu to play for the club. Younger brother John, perhaps better known to New Zealanders as the former co-presenter of nineties UK TV classic Gladiators, played for the club on loan in 1982.

Suddenly, Miramar’s boss had the chance to bring a player of real pedigree to the Peninsula.

However, reservations remained. Not about his sexuality or regularity in UK red tops, these were strictly sporting reservations. Severe knee injuries had forced Fashanu into a nomadic later career experience. In the eight years prior to his Kiwi adventure, Fashanu played for 15 clubs across England, Canada, Scotland, Sweden and the United States.

“We did have a bit of a concern not knowing enough about his physical well-being,” explains Cameron.

“So as a club, we agreed it was best to offer Justin to come out here so we could meet him first-hand and organise for a game to be played. Then we could run our eye over him and be comfortable that he was a viable option physically.”

To Cameron’s amazement, Fashanu agreed. With the start of the season rapidly approaching a hastily arranged friendly between Miramar and a Wellington Invitational XI took place in Petone one Tuesday night.

“It was quite incredible,” Cameron recalls.

“I think there was a crowd of about 4,000 people that turned up and Justin shined, including getting a goal and we quickly endeavoured to put a deal together to bring him over for the summer season.”

Some entrepreneurial contacts helped put a financial package together involving accommodation and a motor vehicle. A few weeks later, Fashanu was lining up at Melville for his New Zealand National League debut.

As a team-mate, Fashanu is remembered as a hard-working, happy and willing striker with none of the baggage or primadonna tendencies you might expect for a player once worth six figures.

His skincare regimen appears to be of particular note. Several ex-colleagues reminisce about it with joy. Fashanu, an imposing physical specimen, drew envy from his more traditionally built team-mates who would joke about whether ‘Fash’s potions would work for them.’

Future New Zealand international goalkeeper James Bannatyne was just a youngster when Fashanu joined the club. The age gap meant he didn’t know Fashanu well but his qualities on the pitch shone through.

“I have two memories of Justin that really stand out,” says Bannatyne.

“One was that lotion,” he jokes.

“The other was a header that was probably better than Grant Turner’s famous one against Australia. What a header, one of the best you’ll ever see.

“It was an absolute demonstration of his raw quality. Look he was in his mid-30s but he still had that timing and quality.”

On the pitch, Fashanu performed well, scoring 12 goals in 18 games but it was a disappointing season for Miramar Rangers as a team, missing out on a play-off spot.

Off the pitch, however, is where Fashanu’s impact was really seen. Cameron recalls the increased fanfare and attendance whenever ‘Fash’ was playing. He added a glamour and celebrity to the local football scene perhaps previously unseen.

Away from the glare, Fashanu was also keen to give back. He helped two Kiwi talents earn soccer scholarships at US universities, he judged at a fashion event at the Wellington Cup and was a regular visitor to the child cancer unit at Wellington Hospital. When he died, a father of one young boy being treated for a brain tumour spoke of his son’s anguish at the passing of ‘My Justin’.

It was a far cry from the depiction often portrayed in the British media. Although he certainly had his flaws, the admission he had tried to sell fake stories to a national newspaper about alleged gay relationships with MPs cost him his job at Scottish side Hearts, his eight months in New Zealand passed without scandal.

“There were always rumours that appeared to follow him but not when he was out here,” says Cameron.

“He was gregarious, no doubt, and always a human headline, but all I can say is that in New Zealand, he was a human headline for all the right reasons and was just a really good thing for football.”

In Cameron, Fashanu had a coach clearly disinterested in the often-reported aspects of his personal life. That had not always been the case in England.

Not only did Fashanu suffer homophobia from members of the UK press and football fanbase, but he also faced it from his own managers. The legendary Brian Clough, who made him a £1m player with his move to Nottingham Forest in 1981, eventually admitted his cruelty toward Fashanu. He once infamously threatened to call the police on him when Fashanu refused a transfer to Derby County. Fashanu found no such trouble in Wellington.

“His sexuality was never really a thing,” says Cameron.

“I never witnessed or recall, and I’m sure I would've found out if it had happened, of any kind of hostility or anything like that.”

Fashanu’s experience has long been a cautionary tale against coming out in the men’s game. He is often held up as the example of why there are so few openly gay male footballers. Indeed, it is striking that it took until roughly a year ago for Blackpool youngster Jake Daniels to become the next professional male UK active footballer to come out as gay, 32 years since Fashanu became the first and previous in 1990.

But Fashanu’s time in New Zealand appears to have been devoid of the bigotry that had plagued large parts of his time in the UK.

As former teammate and All White David Chote details, it was simply a non-issue in the sheds at Miramar.

“I had been in the UK in the eighties and Justin was a big name then and the attention he got was nasty really,” Chote explains.

“I think he felt comfortable in the New Zealand environment. Away from any dramas in relation to his private life where he could play football and have an adventure.

“He wasn't at all in the closet or anything like that. There was no secrecy or scandal because his private life was public. If he had boyfriends they'd be at the club, if he didn't they wouldn't be at the club. He was open, totally open.

“It's sort of a smaller environment here where there wasn’t really that much interest in his sexuality really.”

After eight months, Fashanu left New Zealand and in doing so he played his final game as a professional footballer. He took up a coaching role in Maryland, USA, hanging up his boots with his final game being against Woolston in March of 1997.

The following March, Fashanu’s life courted controversy again. He was accused of the alleged sexual assault of a 17-year-old in Ellicot City, Howard County.

In a state where homosexuality was still illegal, Fashanu denied the allegations.

On May 2 1998, 14 months after his time in New Zealand came to an end, Fashanu, 37, was dead. His cause of death was suicide.

His death shocked those that knew Fashanu during his time in the capital.

“He struck me as a good guy who really cared about people and had a nice tone about him,” says Bannatyne.

“I can’t speak for everyone but I know I was really shocked and sad.”

While his death was reported crudely in the UK, in New Zealand, tributes poured in for a man who, in the words of his boss Cameron, “just wanted to be liked and loved.”

Many dismissed the Maryland allegation but his name has never been cleared. That said, Fashanu has been entered into England’s National Football Hall of Fame. A petition for his statue to be erected outside Norwich’s Carrow Road ground gathered pace late last year. A dramatic televisual retelling of his life and relationship with his brother has just been commissioned. He remains divisive but beloved. A trailblazer to many, and a menace to others.

Fashanu’s truncated life was often lived in the spotlight but, in New Zealand, it appears Fashanu found that elusive slice of heaven. Not only was his sexuality not a problem but seemingly, a non-issue.

“If people feel comfortable with me as a person, then my sexuality is not important,” Fashanu once said. In New Zealand, that’s what he got.

It was perhaps the perfect way to end his playing career, one which ignited so dramatically with that timeless goal against Liverpool before courting such divisive controversy in relation to his sexuality. Fashanu finished his playing career as he started it, carefree and with a smile on his face.

As with most things when it comes to a footballer, his time in New Zealand is perhaps best summed up by a team-mate, an opinion forged in battle from grounds across the nation.

“I recall Justin laughing a lot and smiling a lot,” recalls his old attacking comrade Chote.

“I remember him being friendly and gregarious. All these adjectives for someone who is having a really good time.

“He was and still is a very positive memory for me, both on and off the pitch.”

WHERE TO GET HELP (NZ)

For counselling and support

Need to talk? Free call or text 1737 any time

Chinese Lifeline – 0800 888 880

(for people who speak Mandarin or Cantonese)

For children and young people

Youthline – 0800 376 633, free text 234 or email talk@youthline.co.nz

(for young people, and their parents, whānau and friends)What's Up – 0800 942 8787

(for 5–18 year olds; 1 pm to 11 pm and online chat service from 11am-10.30pm, every day including public holidays)The Lowdown – visit the website, email team@thelowdown.co.nz or free text 5626 (emails and text messages will be responded to between 12 noon and 12 midnight)

SPARX – an online self-help tool that teaches young people the key skills needed to help combat depression and anxiety

WHERE TO GET HELP (UK)

Samaritans – for everyone

Call 116 123

Email jo@samaritans.orgCampaign Against Living Miserably (CALM)

Call 0800 58 58 58 – 5pm to midnight every day

Visit the webchat pagePapyrus – for people under 35

Call 0800 068 41 41 – 9am to midnight every day

Text 07860 039967

Email pat@papyrus-uk.orgChildline – for children and young people under 19

Call 0800 1111 – the number will not show up on your phone billSOS Silence of Suicide – for everyone

Call 0300 1020 505 – 4pm to midnight every day

Email support@sossilenceofsuicide.org

Message a text line

If you do not want to talk to someone over the phone, these text lines are open 24 hours a day, every day.

Shout Crisis Text Line – for everyone

Text "SHOUT" to 85258

YoungMinds Crisis Messenger – for people under 19

Text "YM" to 85258

Talk to someone you trust

Let family or friends know what's going on for you. They may be able to offer support and help keep you safe.

There's no right or wrong way to talk about suicidal feelings – starting the conversation is what's important.

Who else you can talk to

If you find it difficult to talk to someone you know, you could:

call a GP – ask for an emergency appointment

call 111 out of hours – they will help you find the support and help you need

contact your mental health crisis team – if you have one